I’ve watched, and sometimes was involved in, countless conversations about creativity that devolve into the same tired refrain: “Quality matters more than quantity”, “creativity can’t be controlled”, and my personal favourite “I prefer creating high-value work rather than churning out rubbish”.

This thinking is nonsense.

Behind these protests lies a seductive delusion that some people possess the gift. That creativity springs forth like water from a divine well, untainted by the grubby business of practice. I’ve heard photographers describe themselves this way, and worse, I’ve watched admirers project this mythology onto their heroes. It’s a comforting fiction that absolves us of the uncomfortable truth about how mastery actually works.

There is no such thing as natural creativity or an innate gift for art. Or if it exists, it concerns perhaps a dozen people in recorded history, and statistically speaking, you’re not one of them. Neither am I. The sooner we accept this, the sooner we can get on with the real work.

Creativity, art, and quality all require one thing: practice. Lots of it. And practice is both knowledge and quantity rolled into one relentless process.

I get particularly frustrated with people who say things such as “I prefer producing creative work to creating lots of images” or “I don’t learn the rules because I prefer being creative”. This isn’t how quality emerges. It’s how mediocrity perpetuates itself while wearing the mask of artistic integrity.

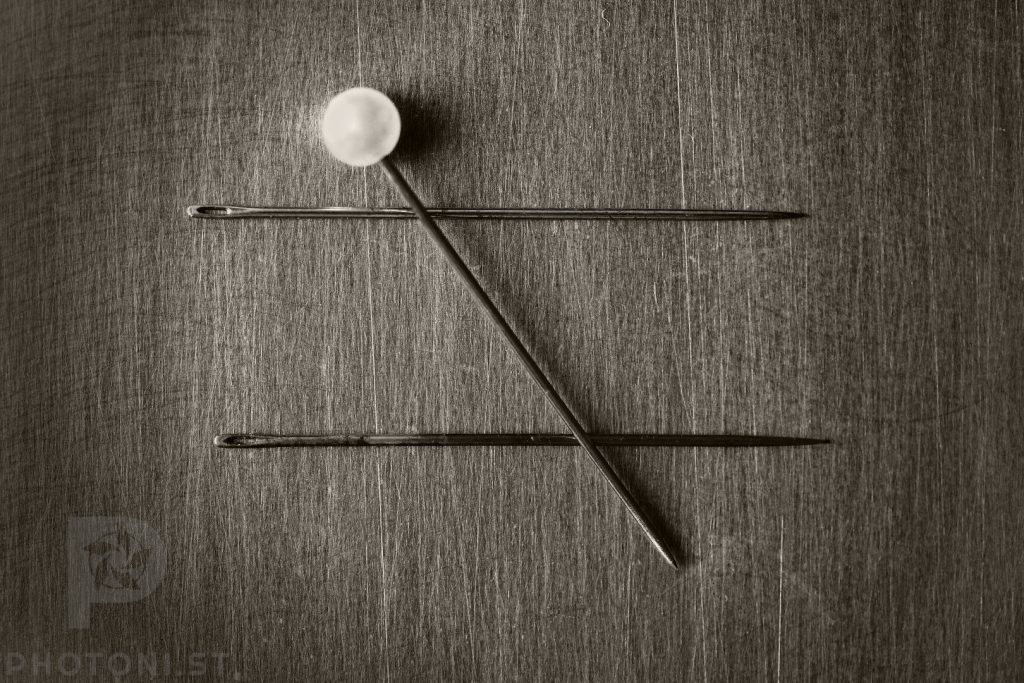

Quality arrives through practice. Brutal, repetitive, often thankless practice. Hours upon hours of trying and failing. Thousands of photographs taken for two or three decent ones. We occasionally discover hundreds of negatives in a famous photographer’s archive after their death, or learn that a celebrated painter worked over the same canvas dozens of times before producing something that endured.

Quantity is how you make the process automatic. It’s how you liberate your mind from the mechanical aspects of creation so you can focus on the creative ones. When you first learn to drive, you struggle with the controls and traffic rules. Your brain becomes overwhelmed trying to coordinate steering, pedals, indicators, and mirrors whilst reading road signs and navigating actual roads and other cars. But through repetition, you internalise those processes. Eventually, you stop thinking about how to drive and concentrate entirely on where you want to go.

Creativity operates identically. Master the tools, internalise the techniques, and your conscious mind becomes free to explore possibilities rather than wrestle with basics.

You also can’t progress without understanding the rules. You don’t know better than hundreds of years of artists who came before you. You can’t invent your own artistic field simply by willing it into existence one Tuesday morning. You need to understand what art is, how it’s produced, which techniques create which effects, how light works, how paint behaves, how stories are structured before you can execute any of it well.

Take Picasso, whom people often cite as proof that creativity trumps technical skill. They point to his revolutionary approaches to painting, his complete departure from traditional representation, his obvious creativity. What they conveniently ignore is that before he created his most famous work, Picasso was an accomplished traditional painter. He had learned all the rules and applied them for years before he began breaking them systematically.

This isn’t an accident. Innovation requires deep knowledge of what you’re innovating against. You can’t subvert conventions you don’t understand. You can’t break rules you’ve never learned. The most radical artists throughout history were first competent practitioners of their craft.

The myth of the gifted creator serves nobody except those who want to avoid the hard work of getting better and those who want to sell you youtube videos and workshops. It provides a convenient excuse for why your work isn’t improving: you either have it or you don’t, and if you don’t, well, that’s just how nature distributed talent.

This is flawed thinking disguised as artistic philosophy.

Real creativity emerges from deep knowledge combined with relentless practice. It’s messy, time-consuming, and often boring. It requires producing vast quantities of mediocre work to arrive at occasional pieces of genuine quality. It demands learning techniques you might never use, studying masters whose work you might not even like, and accepting that competence must precede innovation.

The alternative is comfortable self-deception. You can continue believing that creativity is some mystical process that strikes when conditions are perfect, that quality emerges from careful contemplation rather than repeated action, that technical skill somehow corrupts pure artistic vision.

But I’ve seen where this leads. It leads to people who talk endlessly about their artistic vision whilst producing very little actual art. It leads to photographers who take twelve carefully considered shots per year whilst complaining about “Instagram photographers” who shoot daily. It leads to writers who spend more time discussing their novel than writing it (Brian Griffin anyone?).

The path forward is simple, though not easy: produce more work. Learn the rules. Practice the fundamentals until they become unconscious. Study what works and why. Accept that most of what you create will be forgettable, but that this forgettable work is the foundation upon which memorable work is built.

You don’t have the gift. Neither do I. But we can develop the skills, and skills trump gifts every time because skills can be improved through deliberate action whilst gifts remain static fairy tales.

The question isn’t whether you’re naturally creative. The question is whether you’re willing to do the work that makes creativity possible.

#Photography #Theory #PhotographyTheory #IMayBeWrong #Opinion