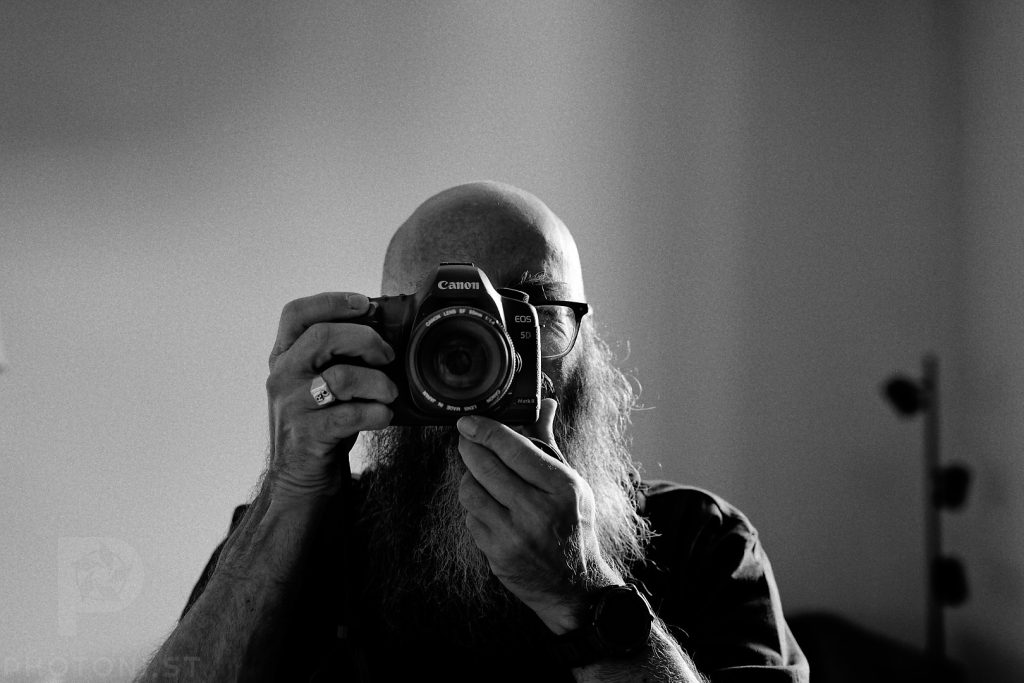

We’ve all heard many photographers talk about storytelling in their photography. How many YT videos can you find on the subject? It’s become such accepted wisdom in the creative world that questioning it feels almost heretical. But when we look at it closely, it doesn’t make sense, and it’s all about how we actually experience photographs.