Sometimes, photography reminds me of scientific research. Both disciplines demand an intense focus on minute details, adhering to conventions that outsiders rarely understand, communicating in a formalized way, and both often seem incomprehensible to the general public.

Just as researchers, in their line of work, focus on minute details that to them mean everything, to the point where most people would consider the activity pointless knit picking (I have a PhD and did a postdoc, I’ve been there), photographers lose themselves in the details of composition, lighting, colours, and technique. A scientist might go over a paper word by word to understand exactly what was intended by their authors, then decide that there is a minuscule gap in in the information where they can contribute with their own work and maybe open a new field of research if they’re insanely lucky. A photographer might look at tiny variations of light in a photo, look at the colour complementarity, analyse the patterns, and pay attention to symmetry that no one else would notice.

Meanwhile, mainstream audiences are often drawn in for different reasons: highly saturated, staged, and instantly gratifying images that flood social media. In the era of social media, they are inundated with photos all day every day. It’s not possible to pay attention to more than an image a day when thousands are thrown at you. In the same way, scientific breakthroughs that capture the public’s attention tend to be the flashy ones (discoveries about black holes, medical breakthroughs, or artificial intelligence) while the methodical, painstaking work behind them remains largely unnoticed.

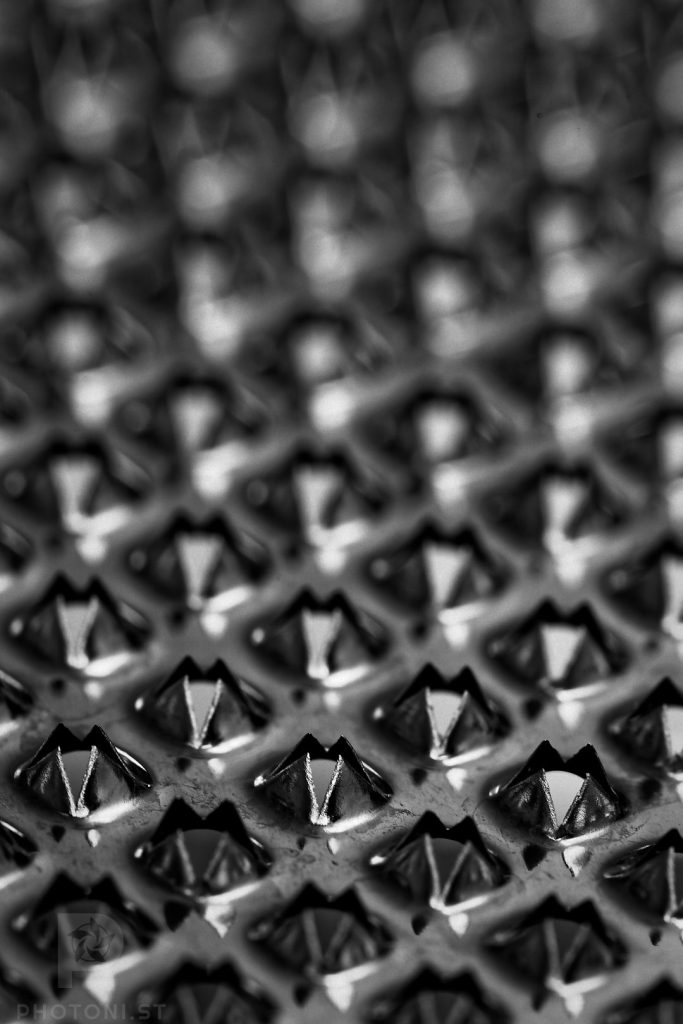

Scientific communities also have their own jargon, as do photographers. Researchers might discuss control groups, statistical significance, and reproducibility, while photographers analyze depth of field, dynamic range, and the nuances of tonal gradation. Two photographers could sit in front of an image and talk about it for hours, dissecting every minute detail, technique, and compositional choice. They might appreciate the subtlest nuances, gradations of shadow, the weight of a particular composition, the way the image draws the eye, while someone else might see only an unremarkable photo.

To an outsider, these conversations can seem cryptic, almost as if they are in a foreign language. That jargon makes it harder for outsiders to participate, even if they wanted to. Not only they’d need to have the right words to capture the concepts (that reminds me of endless discussions with my philosophy lecturer in high school about whether language was a requirement for abstract thought), but the scientific and photography communities alike would not communicate with someone they see as not part of their group. They’d ignore or deride them (you’ve seen it happen).

Moreover, both photography and scientific research are driven by an internal passion for discovery and understanding. Scientists conduct experiments not just for the end results, but for the process of exploration itself. Similarly, for serious photographers, the journey of creating an image (the anticipation, the waiting, the adjustments, the endless trial and error, sometimes the travelling) is often as fulfilling as the final photograph. There’s a quiet, obsessive joy in refining one’s craft, regardless of whether the outside world takes notice.

This also explains why both scientists and photographers sometimes struggle to explain their work to those outside their respective fields. How do you convey the excitement of discovering a new method, a unique light pattern, or a subtle composition choice to someone who isn’t immersed in it?

The general public doesn’t understand that drive. For example, my wife doesn’t understand why I spent so many hours building remote observatories and solving endless issues, or writing my own drivers and software, when I could have spent more money to get something ready made. She doesn’t understand “the pleasure of finding things out”, as Richard Feynman used to say.

In fact the general public doesn’t care about any of that. All this requires a certain education that most people don’t have (intelligence and education are two unrelated things). They don’t have the concepts to pay attention to minute details and understand the intent behind an image and its construction. Not that it’s difficult to acquire, but it takes time and dedication. How many hours did you spend reading books, watching videos, discussing photos with others, before you started understanding and appreciating Daidō Moriyama’s photos? How many articles did you read before you started to have a glimpse of what wabi-sabi is? What effort did it take to understand the rules of photography (thirds, exposure, etc) and when to break them?

And maybe the public doesn’t need to care. They don’t consume photographs like photographers do. They look at images for instant gratification. A jolt of dopamine. Nothing more. If they didn’t get that quick high, they wouldn’t look at photos at all; they’d do something else.

In the end, both scientific research and photography are about seeing what others don’t. Scientists uncover hidden truths about our universe; photographers reveal perspectives that might otherwise go unnoticed. Both require discipline, patience, and a willingness to engage deeply with a subject that few others might care about. And in that shared obsession lies a unique kind of fulfillment, one that isn’t about broad recognition, but about the pursuit of deeper understanding.

#Photography #Opinion #IMayBeWrong #PhotographyTheory