It seems that the majority of amateur photographers go through the same predictable journey that you can track through their gear. They begin their journey convinced that better gear will make them better photographers. Some end it knowing the opposite is true.

Stage 1. Fresh-faced photographers start with whatever they can afford, which sometimes means second-hand gear that’s seen better decades, or the cheapest of the range. I began with a Canon 350D which for me was super expensive but it was pretty much the only DSLR alternative in 2003. The kit lens was pretty soft by today’s standards and most young photographers today would not be found dead with it, but it was mine. This stage breeds resourcefulness. You learn to work within constraints because you have no choice. Every shot matters because you can’t rely on fancy features to save you. My 350D, rated by Canon at 25,000 clicks, took over 100,000 photos and is still working fine. This is when I learned technical photography.

Stage 2. The tragedy is that most photographers are desperate to escape this stage. They spend hours scrolling through gear forums, convincing themselves that their limitations come from their equipment rather than their inexperience. They’re only partially right. Eventually, photographers scrape together enough money for their first “good” camera. Usually, it’s the most expensive thing they can justify buying. The bigger and more professional it looks, the better. I’ve been there.

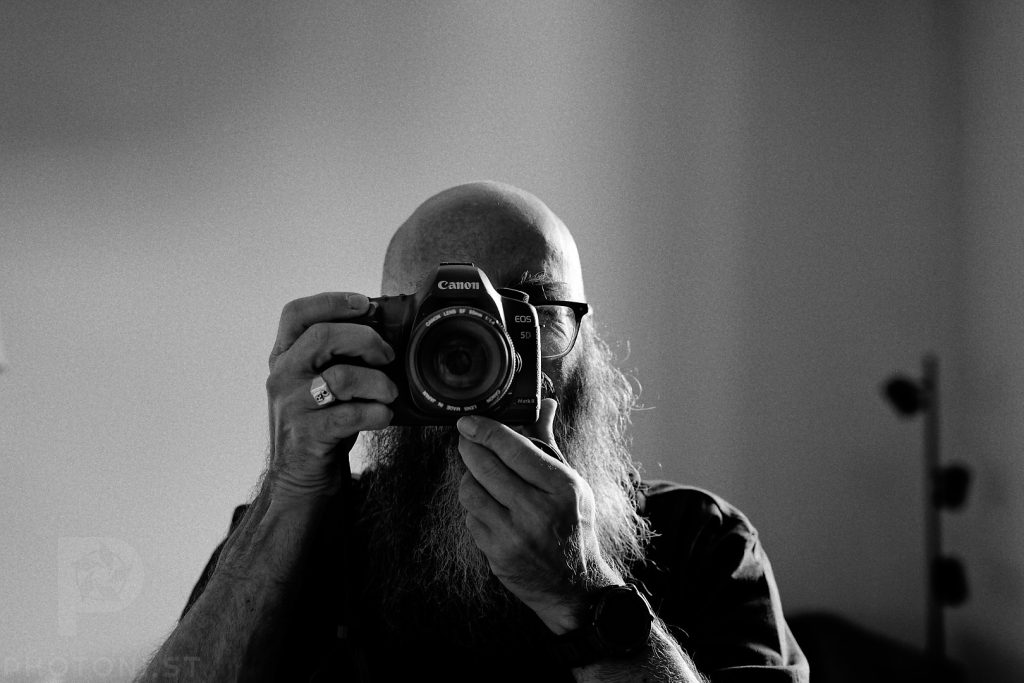

I remember the day I bought my first full-frame camera. It was the newly released 5D in 2007. My girlfriend at the time (now wife) had been pushing me for weeks to buy one because she knew how much I lusted on it. It was absurdly heavy, especially with a good zoom lens on it, had more buttons than a mixing desk, and cost more than my first car. I felt like a proper photographer for the first time. The weight of it hanging around my neck was a badge of honour. This phase is about signalling as much as shooting. You want other photographers to know you’ve arrived. You want people to take you seriously. You want to belong to the club of people who own expensive things.

The irony is that this gear actually does improve your photographs, but not for the reasons you think. Better dynamic range and cleaner high ISO performance give you more technical flexibility. However, the real improvement comes from finally having equipment that doesn’t fight you at every turn. When your camera stops being an obstacle, you can focus on actually learning photography.

I took another 150,000 photos at that stage with the 5D. That’s when I finally understood how to compose and create photos.

Stage 3. After a few years of lugging around professional equipment, photographers often pivot to vintage gear. Film cameras become particularly attractive. There’s something seductive about the mechanical precision of a Leica M6 or the chunky reliability of a Pentax K1000. This stage is driven by a different kind of signalling. Instead of showing off expensive new gear, you’re demonstrating your artistic credibility. For some film photography suggests you understand the fundamentals. Vintage equipment implies you care more about craft than convenience. The photography community encourages this behaviour. Film photography is fetishised to an absurd degree. There’s an entire industry built around convincing photographers that digital is somehow inferior to analogue processes. It’s mostly nonsense, but compelling nonsense.

In other cases, it’s old digital cameras (now called digicams). Using those somehow signals that you’re different from every other photographer because you have discovered something most haven’t yet. You persist in using cameras that place ridiculous constraints on your photos due to limitations (extremely bad sensitivity), quality (really bad lenses), or just dynamic range. But low quality becomes the badge of honor of that stage. You’re an artist that suffers for your art.

I mostly skipped this stage because my photography was a hiatus at that time. Other things got in the way.

Stage 4. The final stage is when photographers stop caring about gear entirely. They realise that the best camera is the one you have with you, and the lightest camera is the one you’re most likely to carry. This realisation usually comes after years of missed shots because your camera was too heavy to bring along, or too conspicuous to use discreetly. You also realise that artifacts are not art. You start to understand that photography is about seeing, not about the tools you use to capture what you see.

I carry either a small Sony RX100III or a 5DII when I travel now, often with just a single prime lens (28mm). The image quality is not exceptional, both cameras being between 10 and 15 years old, but more importantly, they’re always with me and I trust them.

At this stage, The equipment becomes invisible. You stop thinking about aperture rings and focus peaking and start thinking about light and composition and timing. This is when you actually become a photographer rather than someone who owns cameras.

It’s also at this stage that you find who you are as a photographer. You care a lot less about what others think about what you produce, and spend more time discovering what your strengths are, what provide you with pleasure, and what works for you.

It can take a very long time to reach this final stage. Photographers get stuck in the cycle of buying and selling equipment, convinced that the next purchase will unlock their creative potential. The photography industry depends on this delusion. Camera manufacturers release new models every year, each promising revolutionary improvements. Photography forums are filled with pixel-peeping comparisons and upgrade discussions. YouTube channels generate millions of views reviewing equipment that’s functionally identical to last year’s models.

The dirty secret is that cameras stopped getting meaningfully better 10 years ago. A ten-year-old camera can produce images that are indistinguishable from the latest models in most real-world situations (I defy you to find meaningful differences between a photo taken with a 15 year old 6D and one taken with a R6). The improvements are incremental and largely irrelevant to the actual practice of photography.

Understanding these stages helps you recognise where you are in your own journey. More importantly, it helps you skip ahead. You don’t need to spend years accumulating expensive gear to become a better photographer. But there is of course a case for the necessity of going through these stages: what you learn at each stage is a prerequisite of successfully moving on to the next. If you don’t go through the gear buying stage, no matter how many times other people tell you buying stuff is pointless, you won’t believe it. You need to discover it for yourself. If you don’t go through the vintage gear stage, you won’t discover how pointless recent hardware is and you can’t move on to the proper photography stage.

The most interesting photographers are those who have reached the final stage. They’re the ones getting the shots while others are still adjusting their camera settings. They understand that photography is about being present, not about having the perfect kit. If you’re still caught in the earlier stages, I’m not suggesting you sell all your gear tomorrow. But I am suggesting you stop waiting for the next upgrade to start taking the photographs you want to take. The gear you have is probably good enough. The question is whether you are.

#Photography #Opinion #IMayBeWrong #Theory