Your audience self-selects partly based on shared cognitive architecture. This isn’t about intelligence or sophistication. It’s about whether your mode of thinking and communicating matches theirs closely enough that recognition happens.

Your audience self-selects partly based on shared cognitive architecture. This isn’t about intelligence or sophistication. It’s about whether your mode of thinking and communicating matches theirs closely enough that recognition happens.

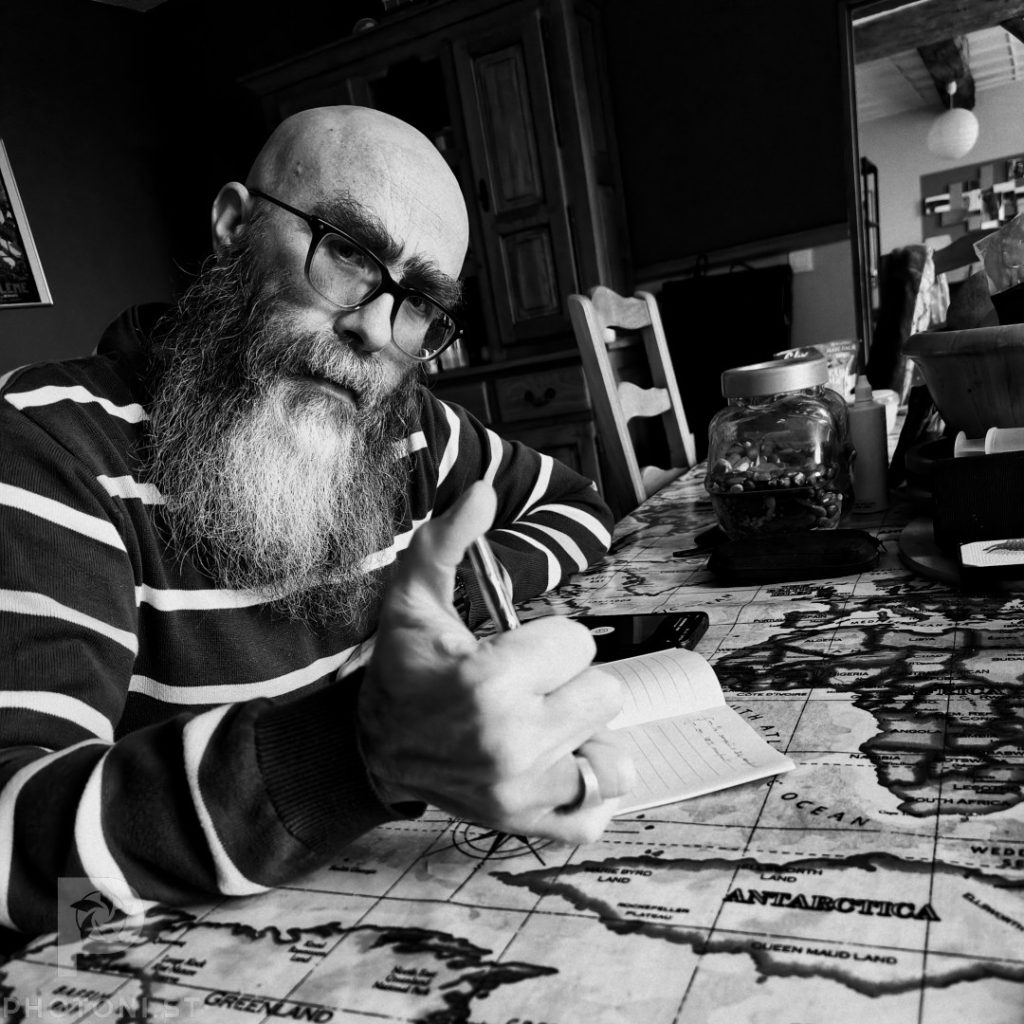

My mother sometimes jokes that she raised a ghost, because there are barely any photographs of me as a child or teenager. I just hated having my photo taken and I’d find ways to hide to avoid it. When I started photography ca. 2002, I started taking photos of people around me. But I continued to hide from them when they wanted to take photos of me. My relationship with them was imbalanced.

It took me another 15 years to realise I was being stupid.

Photography instruction assumes cognitive uniformity. Teachers describe their own process and expect students to replicate it. “Learn to see the light.” “Pre-visualise the image.” “Feel the moment.” These instructions make perfect sense if your brain works like the teacher’s brain, but they become incomprehensible if it doesn’t.

I can tell you exactly how I felt standing on a sand dune in Morocco many years ago, watching my wife photograph a sand dune through evening light. I remember the temperature, the angle of the sun, the smell of dust. I remember the specific quality of happiness that comes from being exactly where you want to be with exactly who you want to be there with. That moment is still accessible to me. I was there. It happened. The photos prove it.

Photography education and criticism privilege verbal articulation. You’re expected to be able to explain your work, discuss your influences, articulate your intentions, write artist statements. Grants and residencies require written proposals. Publications want accompanying text. Teaching positions demand that you can explain your process clearly.

But many talented photographers can’t write coherently about their work, and it’s not because they haven’t thought deeply about it or because they’re inarticulate generally. It’s because the work happens in a non-verbal mode and translating it into words requires cognitive machinery they don’t have or have configured differently.

Not legally, though we’ll get to the murky ethics of that. I mean conceptually, technically, aesthetically. Every image I’ve made is somewhere on a spectrum between homage and plagiarism, filtered through techniques I borrowed from photographers who borrowed them from other photographers who borrowed them from painters who probably borrowed them from someone else. Nothing I’ve done is original. I’m not sure anything in photography is.

Ansel Adams talked about pre-visualisation as the foundation of his photographic method. He could see the final print before making the exposure, knowing exactly what the image would look like after development and printing. Not just approximately but precisely. The vision came first, complete and detailed, and the technical process existed to manifest that internal image in physical form.

If you can do that, if you can see the finished photograph in your mind before you press the shutter, your entire approach to photography centres on capturing that vision. You’re trying to match what you see in your head with what the camera records. The image exists first internally, then you make it real through technical execution. Vision precedes and guides craft.

Photography isn’t one thing anymore. It hasn’t been for a while, but we’re still using the same word for fundamentally different activities, which creates confusion about what’s happening to the medium and why it matters.

There are four distinct categories of photography now, defined by who makes the image and who consumes it. Understanding these categories and how they’re bleeding into each other is more important than endless hand-wringing about what AI generation does.

Most people assume everyone thinks the same way they do. They imagine that when you say “picture this in your mind,” everyone experiences roughly the same thing. When you say “think about it,” everyone has the same internal process. But cognitive variation is enormous, and these differences fundamentally change how you approach photography.

On my way back from Lyon recently, I experimented with trying to convey meaning over prettiness.